Princeton researchers conducted an experiment on mysterious objects dubbed as "frustrated magnets" to figure out why they are discontented.

The study, published in the Science journal this week, is expected to help advance the understanding for high-temperature superconductivity mechanism in electricity.

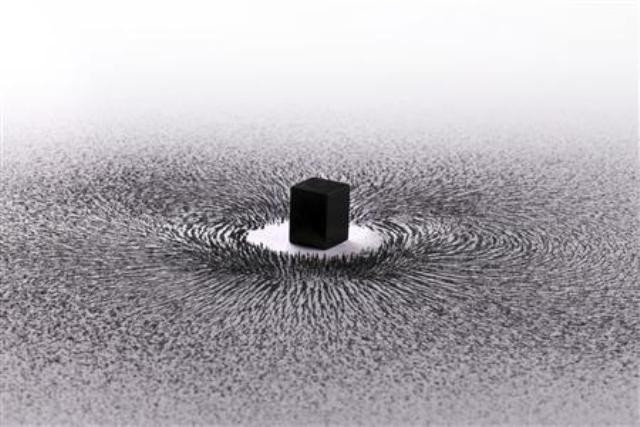

Frustrated magnets are supposed to be magnetic at lower than average temperatures, but do not exhibit any magnetism. The researchers tested them to determine whether they can exhibit the Hall Effect, according to Phys.org.

E.H. Hall discovered the effect in 1879. Whenever an electric current is affected by a magnetic field, the current then deflects to only one side of a copper ribbon.

Hall Effect is now used in sensors in electronic devices such as remote controls, motion sensors and even anti-lock braking tech in vehicles.

"To talk about the Hall Effect for neutral particles is an oxymoron, a crazy idea," said N. Phuan Ong, Professor of Physics at Princeton.

Ong said that frustrated magnets are interesting because several theorists speculate that the material should have their "spins" aligned in the same direction.

However, the experiment on the pyrochlores showed that the spins only pointed at seemingly random directions. Ong said that they do not align because of "geometric frustration."

Further research on the said frustrated materials might shed light on how superconductivity happens in specific high-temperature superconductors known as cuprates. These copper-containing materials are used in MRI machines, according to Science Codex.

One theory on how superconductivity occurs on high-temperature is the potential existence of the spinon particle. Several theorists such as Joseph Henry from Princeton, Nobel laureate Philip Anderson and other scientists believe that spinons can carry the heat current for a quantum system.

Despite the researchers not being able to observe the said particle, Ong said that they might eventually be able to do so in the future because of the experiment.