Scientists have managed to establish a brain to brain connection between two persons that can allow one person to accurately predict what the other one is thinking. This remarkable experiment was successful enough to transmit signals from the one participant's brain to another over the internet.

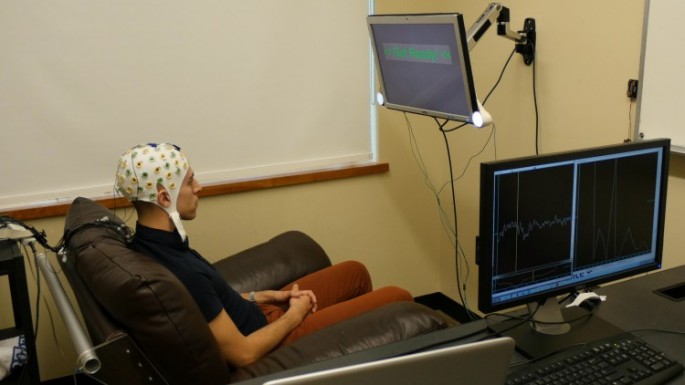

Researchers from the University of Washington made use of an electroencephalography (EEG) machine where the "respondent" wore a cap that was hooked to the machine to monitor brain activity. The respondent was presented with images of a dog on the computer while the other participant who is the "inquirer" is located in a different area, almost a mile away where the researchers also presented a variety of images on a computer, so that the inquirer can guess what the respondent has been looking at.

The inquirer will then click from the variety of objects where the respondent will respond yes or no while focusing on two LED lights that are attached to their monitors, flashing at different frequencies. The yes or no answers will be sent back to the inquirer via the internet and will trigger a magnetic coil that is located behind the inquirer.

The yes answer apparently creates a more powerful response in order to stimulate the visual cortex that allows the inquirer to see a light called phosphene, appearing as a blob or a thin line or wave, letting them know that it is the correct answer.

In order to test the accuracy of this study, researchers asked five participants to play 20 rounds of the game in separate dark rooms. The 20 rounds involve 10 real games and 10 control games where a plastic spacer was placed between the magnetic coil and the inquirer to prevent signals from reaching them, in which they are unaware of.

The results of the study revealed that the inquirers were able to predict the right answer with a 72 percent accuracy during real games and 18 percent accuracy in control games, that were most likely lucky guesses.

According to co-author of the study Chantel Prat from the Institute for Learning & Brain Sciences at the University of Washington, there were times that during the real games, that the answers were predicted wrongly because of complex brain activity. Even if the flashing lights are already giving away signals to the brain, there are still parts of the brain that are accomplishing a million other things at any given time.

This new study is published in the journal, PLOS One.