New series of images released by NASA's New Horizons probe that just completed a historic flyby of the dwarf planet Pluto reveal even more complex features on the surface of the icy world, which appears to be like woodworm infested log.

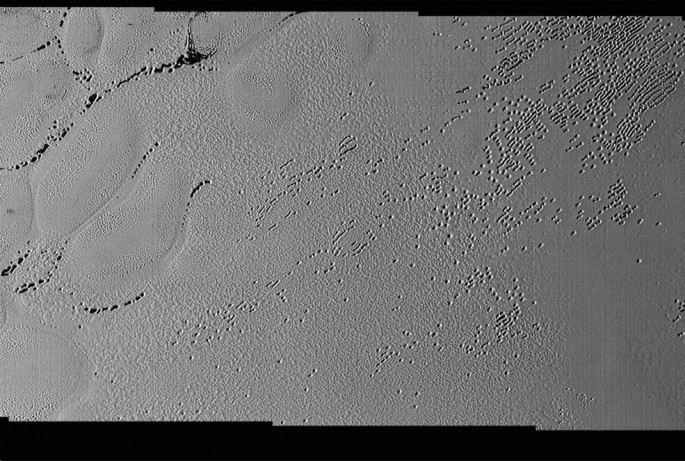

This image was just captured before the probe's closest approach last July 14, showing Pluto's Sputnik Planum regions and providing unprecedented views of more than 100 icy pits, measuring a few hundred meters wide and reaching tens of meters deep into the surface.

These pits are composed of ice made from nitrogen as planetary scientists are still seeking clues about how these features were formed via sublimation however, scientists are still not convinced that this event links to the pits' alignment and location.

The event known as sublimation occurs when ice directly transforms into vapor and not in its liquid state, similar to "dry ice" or carbon dioxide ice here on Earth, as ice changes immediately into gas skipping its liquid state. Since the atmospheric pressure on Pluto is light, sublimation becomes a dominant process where abundant surface ices are now heated and escape via gases into the thin atmosphere.

This can somehow explain how there is a surprising absence of impact craters on Sputnik Planum since Pluto's surface is constantly replenished with new ice with new layers due to the atmosphere where pits offer evidence how this ice layer is actually active.

According to project scientist for New Horizons, Hal Weaver from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, Pluto is really weird but in a good way. The pits and their alignment show evidence of ice flows and the exchange of volatiles between the surface and the dwarf planet's atmosphere, revealing complex physical processes at play.

The region can be described as complex with flat plains but the new discovery of these pits makes Sputnik Planum an icy ocean filled with sinkholes that spans across the horizon.

Pluto came as a surprise to scientists and the rest of humanity as how dynamic a distant, icy world can be. Located in the Kuiper Belt some 50 times farther away from the sun to the Earth, the dwarf planet still possesses significant geological activity and how even the tiniest amount of heat can dramatically change the terrain of a distant, ancient world.