Over the last decade, flight surgeons and scientists at NASA have been puzzled by visual impairments in nearly two-thirds of astronauts on long-duration missions aboard the International Space Station (ISS) and they now know the reason why.

They believe this malady, called "visual impairment intracranial pressure" syndrome (VIIP), might be related to volume changes in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) found around the brain and spinal cord.

The astronauts with VIIP all exhibited blurry vision, said a study presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America in Chicago.

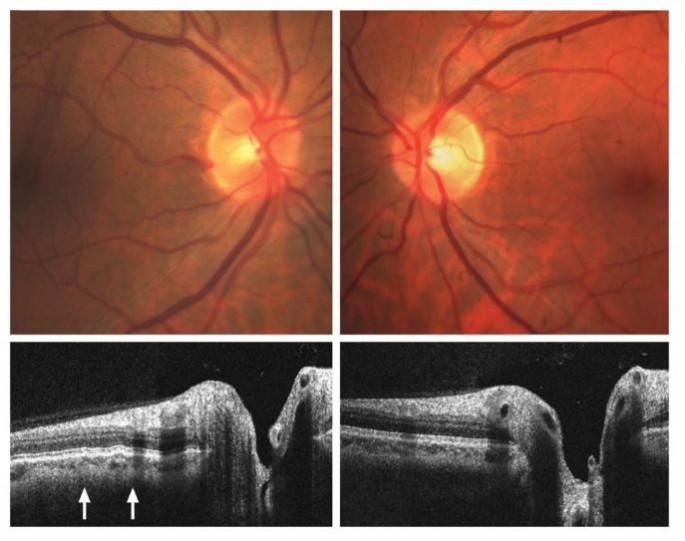

More tests revealed structural changes, including flattening at the back of the astronauts' eyeballs and inflammation of the head of their optic nerves.

"People initially didn't know what to make of it, and by 2010 there was growing concern as it became apparent that some of the astronauts had severe structural changes that were not fully reversible upon return to earth," said study lead author Noam Alperin, professor of radiology and biomedical engineering at the University of Miami.

Scientists previously believed the main cause of the problem was a shift of vascular fluid toward the upper body that takes place when astronauts are exposed for long periods to the microgravity of space.

Researchers, however, investigated another possible source for the problem: CSF.

This clear fluid that helps cushion the brain and spinal cord while circulating nutrients and removing waste materials.

The CSF system can withstand significant changes in hydrostatic pressures, such as when a person rises from a lying to sitting or standing position. In space, however, the CFS system is confused by the lack of the posture-related pressure changes.

Alperin and his colleagues performed high-resolution orbit and brain MRI scans before and shortly after spaceflights for seven long-duration mission ISS astronauts. They then compared results with those from nine short-duration mission Space Shuttle astronauts.

The study showed that long-duration astronauts had significantly increased post-flight flattening of their eyeballs and increased optic nerve protrusion.

Long-duration astronauts also had significantly greater post-flight increases in orbital CSF volume, or the CSF around the optic nerves within the bony cavity of the skull that holds the eye, and ventricular CSF volume, or the volume in the cavities of the brain where CSF is produced.

The large post-spaceflight ocular changes observed in ISS crew members were associated with greater increases in intraorbital and intracranial CSF volume.

"The research provides, for the first time, quantitative evidence obtained from short- and long-duration astronauts pointing to the primary and direct role of the CSF in the globe deformations seen in astronauts with visual impairment syndrome," said Alperin.

Identifying the origin of the space-induced ocular changes is necessary for the development of countermeasures to protect the crew from the ill effects of long-duration exposure to microgravity.

"If the ocular structural deformations are not identified early, astronauts could suffer irreversible damage. As the eye globe becomes more flattened, the astronauts become hyperopic, or far-sighted."

Other doctors think the extra fluid in the skull increases pressure on the brain and the back of the eye. VIIP has now been recognized as a widespread problem, and there has been a struggle to understand its cause.