Researchers have developed a biodegradable sponge-like implant that can identify and capture cancer cells in mice. The new breakthrough could help to slow down the disease's spread to other organs in humans, becoming a step forward in the medical world's search for a cancer cure.

The research was conducted by a team from the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Illinois. Its invention was published in Nature Communications.

Metastatic cancer occurs when the disease's cells move away from the primary tumors, to other regions of the body. It usually happens through the bloodstream.

However, the cancer cells can also migrate through the lymph system. They attach to a lymph or blood vessel, then enter a new organ and create new tumors.

Cancer patients' survival rates are higher when the disease is detected before cancer cells start circulating and infecting other organs. However, that task is difficult.

Prof. Lonnie Shea was the study's co-author. His team explained that a small number of circulating cancer cells stay in the blood before they take up residence in the new organ, and some of them are shed. This makes detection very challenging.

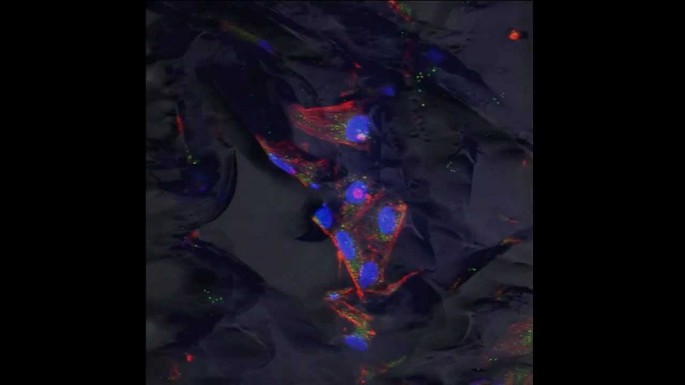

The study describes a "biomaterial implanted scaffold" implant that the researchers invented, according to Medical News today. It identifies and "traps" metastatic cancer cells.

The biomaterial implant is made with a molecule called CCL22, according to PPPFocus. It is already used in other medical devices.

A special tool is then used. It distinguishes the cancer cells and healthy cells that the implant has trapped, according to Medial News Today.

The researchers tested their implant on eight mice that had metastatic breast cancer. Two implants were inserted under the skin or inside the abdominal fat of the mice.

The researchers captured circulated cancer cells. This reduced their number in the bloodstream, and lowered the chance of them creating new tumors in other organs.

Prof. Shea told the BBC that the team hopes to soon test the new implant in humans. Its safety and efficacy would be evaluated.