The dwarf planet Ceres continues to baffle scientists as a variety of images obtained by NASA's Dawn spacecraft reveal some clues why its craters are missing from its surface.

NASA's Dawn mission began last year to observe and capture images during the very first flyby of this icy object located in the major asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. In this new study, scientists are currently debating the mysterious cause of the disappearance of these craters.

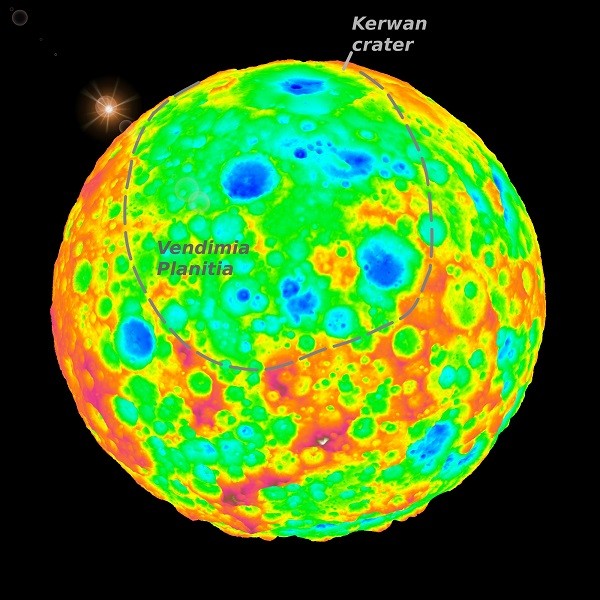

Since Ceres is located inside an asteroid belt, this would also suggest how this is a region where most collisions and impacts occur, and some of them may even be really violent. As new data from Dawn were transmitted, there were no large craters visible from the imagery, just smaller ones where the biggest crater is measured to be only 15 miles across.

Scientists from the Southwest Research Institute conducted computer simulations based on the impacts of Ceres, confirming how these missing craters should be visible on the dwarf planet's surface. This strategic location for Ceres that is ideal for impact activity should yield craters as big as 250 miles across according to researchers, but new imagery from Dawn say otherwise.

According to Dawn lead investigator Simone Marchi from the Southwest Research Institute in Colorado, Ceres is estimated to form during the early stages of the solar system, about one to ten millions years after the formation of the solar system. Ceres is also considered a witness to this violent era where collisions were significantly more frequent than today's.

New findings reveal how the icy dwarf planet and its frozen core may have something to do with this crater disappearance, as the planet's interior apparently show some movement within. During long periods of time, the surface replenishes itself where cryovolcanoes once existed, spewed water and ice, eventually covering the surface with new terrain and material.

This new study is published in the journal of Nature Communications.