Our synapses -- the junctions between nerve cells -- grow strong and large during the stimulation of daytime, but shrink by nearly 20 percent while we sleep, creating room for more growth and learning the next day, according to an extensive study.

The four-year research project published in the journal Science offers a direct visual proof of the "synaptic homeostasis hypothesis" (SHY) proposed by Dr. Chiara Cirelli and Dr. Giulio Tononi of the Wisconsin Center for Sleep and Consciousness.

This hypothesis holds that sleep is the price we pay for brains that are plastic and able to keep learning new things.

When a synapse is repeatedly activated during waking, it grows in strength, and this growth is believed to be important for learning and memory.

SHY, however, contends this growth needs to be balanced to avoid the saturation of synapses and the obliteration of neural signaling and memories. Sleep is believed to be the best time for this process of renormalization, we pay much less attention to the external world and are free from the "here and now" when we sleep.

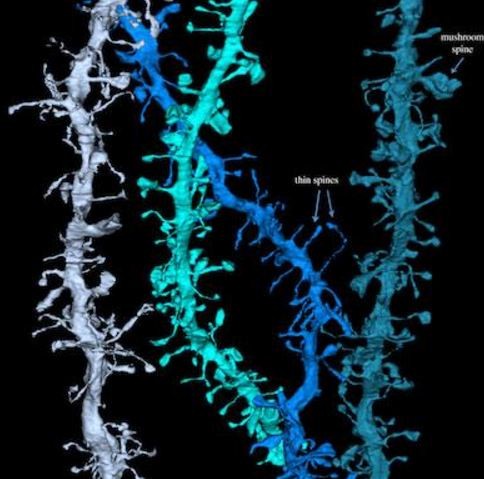

When synapses get stronger and more effective they also become bigger, and shrink when they weaken.

Cirelli and Tononi reasoned a direct test of SHY was to determine whether the size of synapses changes between sleep and wake. To do so, they used a method with extremely high spatial resolution called serial scanning 3-D electron microscopy.

The research was a massive undertaking, with many research specialists working for four years to photograph, reconstruct and analyze two areas of cerebral cortex in the mouse brain. They were able to reconstruct 6,920 synapses and measure their size.

The team deliberately did not know whether they were analyzing the brain cells of a well-rested mouse or one that had been awake. When they finally "broke the code" and correlated the measurements with the amount of sleep the mice had during the six to eight hours before the image was taken, they found that a few hours of sleep led on average to an 18 percent decrease in the size of the synapses.

These changes occurred in both areas of the cerebral cortex and were proportional to the size of the synapses.

"This shows, in unequivocal ultrastructural terms, that the balance of synaptic size and strength is upset by wake and restored by sleep," said Cirelli. "It is remarkable that the vast majority of synapses in the cortex undergo such a large change in size over just a few hours of wake and sleep.

Tononi said extrapolating from mice to humans, "our findings mean that every night trillions of synapses in our cortex could get slimmer by nearly 20 percent."